When the government, the private sector, and the Church move in the same direction, transformation becomes possible, not just in infrastructure, but in the soul of a city.

This was the essence of the statement shared by Joe Soberano, President and CEO of Cebu Landmasters Incorporated, during the opening of Patria de Cebu. His message was more than ceremonial; it was a clear commitment to the Cebu City Government and to the people of Cebu. that progress can be meaningful when it is anchored in cooperation and respect for heritage.

Present at the event was Cebu City Mayor Nestor Archival , alongside the Roman Catholic Church, represented by Archbishop Emeritus Jose Palma. Their presence symbolized a rare but powerful convergence of leadership: public service, private enterprise, and faith working together toward a shared vision.

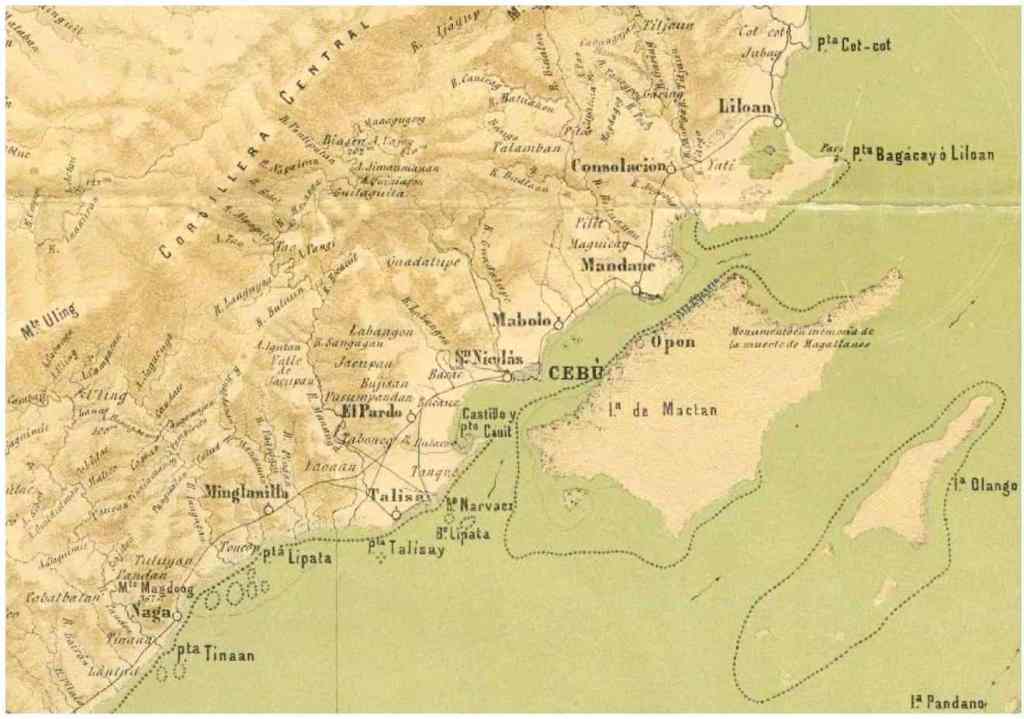

The initial focus of this collaboration is the beautification and revitalization of Cebu City’s downtown, beginning with the historic surroundings of the Cebu Metropolitan Cathedral, a site that has stood witness to centuries of Cebuano faith, culture, and history.

Rather than development that erases the past, this initiative seeks to enhance what already exists, giving dignity to heritage spaces while making them more accessible, livable, and vibrant for today’s generation.

Cebu City is not just an urban center; it is the cradle of Christianity in the Philippines, the heart of early trade, and a living museum of colonial and pre-colonial history. Any effort to uplift the city must therefore balance modernization with preservation.

This tri-sector partnership recognizes that truth: progress does not mean forgetting where we came from, it means building forward with memory and meaning. When coordination and collaboration truly happen, the benefits ripple outward.

Heritage is protected, public spaces are improved, local communities gain renewed pride, and the city strengthens its identity—not only as a hub of commerce, but as a place where history, faith, and development coexist. In this shared effort, Cebu City is reminded of a powerful lesson: the most enduring developments are those built not by one sector alone, but by a united community, honoring its past while shaping its future.

Patria de Cebu is a living symbol of what collaboration can achieve. Redeveloped through a joint effort of the Roman Catholic Church and Cebu Landmasters Incorporated, it transforms a historic space into a place where the past and present meet.

Now open with a supermarket and a growing mix of food outlets, Patria de Cebu is once again bringing life back to downtown. Soon, it will also welcome the Mercure Hotel by Accor, the first international hotel brand in downtown Cebu City, a powerful sign that faith, heritage, and progress can move forward together, restoring pride in the heart of the city.